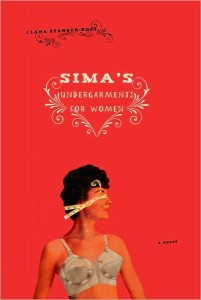

My friend Ilana Stanger-Ross's 2008 novel Sima's Undergarments for Women is out in paperback. I think I would have written something about it here were it not for the fact that I read it around the time my daughter, Roxy, was born. But here's what I wrote to Ilana:

It's stunning! I expected I'd like it, but I had no idea that it would consume me. I read it all with Roxy in one arm and the book in the other, much of it out loud to her. I'd rock her to sleep and then grab the book. If there's any justice in the world -- and there isn't -- it'll win prizes. Beneath the veneer of "charming," as Kirkus puts it, I found a book of surprising pain, reminiscent of Delmore Schwartz' regrets in "In Dreams Begin Responsibilities" and Malamud's restraint in The Assistant. I'm deeply impressed at the courage of creation evident in the character of Sima [the aging, disappointed-in-life owner of a lingerie shop], who never grows cute, never a bubbe or a yenta or any recognizable Jewish literary figure; rather a real woman, and a Jewish one. And I think your decision not to really reveal Timna [her gorgeous young Israeli assistant] to us is brilliant; a lesser novel would have done so. I think the closest I got to Timna was the scene in which she tells Sima that it'd be unfair to envy her; but even then, I stay with Sima, her embarrassment, her resentment. Her resentments are profound.

I was impressed, too, by the honesty with which you depicted work. In fact, I can't think of many novels that pay such close, true attention to work, its costs and its rewards and the large but not total role it can play in a life. That's subtly evident in Lev [Sima's retired husband], too, who seems to have been emptied out not just by life with Sima but by an ordinary career as a teacher; he did his work and now he's tired. There's a line near the end that knocked the wind out of me, Sima speaking to Lev: "It's been too late for so long that I don't think time matters anymore."

Of course, there are many such lines. I mention Malamud because he's such a brilliant storyteller without ever showing off. Schwartz, of course, is pyrotechnic; most younger writers are. This novel never calls attention to you, Ilana, which makes it all the more splendid when a line causes the reader to pause, to consider the fragment of things-as-they-are described just so.

I think, too, that it's an important Jewish book, maybe a pivotal one. In part because you describe a world I haven't really seen in books -- the frummy but not frum majority of Brooklyn Jews -- and in part because the book feels so effortlessly Jewish. So plainly and simply and completely Jewish. (The stuff about Israel is very funny. And that's a sentence that's unusual these days.) No shtetl, no bubbe, no identity angst, no folktales, just a couple of Jews in a basement full of bras.